-

Vorige

Nieuwe gedichten (New Poems)

Martinus Nijhoff

1934 -

Volgende

Karakter (Character)

F. Bordewijk

1938

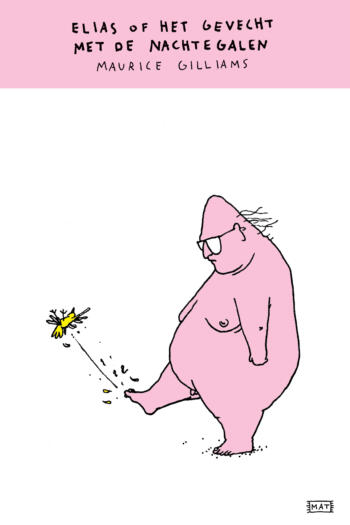

Right from the start, the novel is about “troubling” and “enchantment”, about a “different” experience of reality as perceived by the twelve-year-old Elias. The boy is under the spell of his older cousin Aloysius, with whom he wanders about on a country estate belonging to family. They sail boats on a brook in the park.

Maurice Gilliams was far ahead of his time with this novel, but he also belongs to a tradition. Elias is an autobiographical bildungsroman that does not so much tell a story as depict the inner world of an introverted, over-sensitive young boy who goes into “battle” against the entrancing “nightingales” of his own imagination.

Gilliams rejects the conventional relaying of facts – he called it “stuffing sausages” - in favour of an exploration of the self. The pivotal question is: “Who am I?” In Gilliam’s diary we read: “I am Elias”.

This novel is a search for self-knowledge, along the lines of Marcel Proust’s À la recherche du temps perdu, but also comparable to Rainer Maria Rilke and the prose of Karel van de Woestijne. The young Elias is dominated by a morbid fantasy that makes him unsuitable for “ordinary life”. He lives shut away in the world of “the chateau”, which he wants to escape by way of “the brook”, but he does not succeed. This spatial defeat symbolises the dualism in which he is trapped. The novel also offers a glimpse into the world of the old, French-speaking upper bourgeoisie around the turn of the century, a dying class that lived in social and spiritual isolation.

Elias is unusual in that this discrepancy between the spatial and the substantive is elaborated musically: the two themes are set in opposition using the principle of the sonata form. The paragraphs are arranged according to the structure of a classic sonata, in which two themes or motifs are increasingly modulated, in this case the brook motif and the chateau motif, which alternate and at times merge almost imperceptibly.

This unique formal experiment went unnoticed by contemporary readers, even though Gilliams explained it himself in one of his diaries. The novel was read in the context of the emerging psychological novel, which presented an analysis of the “life of the mind”. But Gilliams went much further than his contemporaries, such as Maurice Roelants and Filip De Pillecyn. He was a master in unravelling the unexpressed impressions at the edge of consciousness. The book does not present a logically told tale but instead a self-contained world composed of the fragments of a young man’s experience.

Elias is an “autonomous” work of linguistic art that anticipates later developments in literature, but more importantly, remains fascinating to this day to many readers and other authors (such as Stefan Hertmans and Erwin Mortier) through both the world of emotions it depicts and its musical influence, which even extends to the rhythm of the sentences.